"So how did you get into Furry, anyways?"

Talking amongst ourselves as furries, there are certain personally-directed questions we tend to ask pretty often. What's your fursona? What artist made that badge? That sort of thing. One of my favorites to answer is, how did you find the fandom? You see, I have a story, a whole spiel I get to go into. And I love to tell stories.

The story goes that, in middle school, I would frequent this one Christian youth group because my friends at the time went there after school. The pastor's intern, a college student, was a friendly man, despite the fact that we, being rude middle schoolers, often did mean things to him. But, being a cool, affable college student who spent many of his afternoons mollifying rude middle schoolers, he would occasionally share with us some of the things he was interested in. We would laugh about how ridiculous some Christian pastors were about pop culture back in the 80s (c.f. Turmoil in the Toy Box). He showed us the really weird depiction of Satan in The Adventures of Mark Twain. But for this story, the most important thing the intern did was introduce us to Cracked.com.

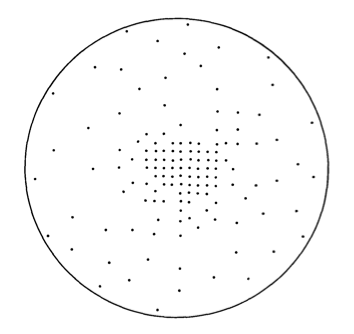

Cracked, apparently, still exists in some form today. I think, much like Deadspin, it exists only in a zombie state; most of the writers I remember from my time with it have since left or been fired. But, back in the time I spent with it, in the early 2010s, it was a popular humour site that made extensive use of the listicle before it became popular. Here's one of my favorite articles from that era of Cracked, a humourous but useful explanation of Dunbar's Number called "What is the Monkeysphere?".

At the time, I found Cracked interesting, and started reading it on my own outside of that youth group. At some point I found one particular article -- cw: this article discusses shitty webcomics, and demonstrates how shitty they are with examples, so included inside are examples of racism, anti-semitism, transphobia, and discussions related to the sexual exploitation of children -- "The 5 Circles of Baffling Web Comic Hell". If you check it out yourself, you can see, but... most of the webcomics featured here are, uh, really bad, both in topic and in artistic quality.

One webcomic featured in it, though, stood out to me: Concession by Immelmann. Its art was... not transcendent, but compared to the rest it was a serious improvement. It featured on this list (under "Circle 2: Incomprehensible Sexual Fetishes") for a bizarre plot point of the story, that somehow having brain cancer caused the main character to end up in a situation where he believed he had sexually exploited a minor. I decided, hell, the story couldn't really be that fucked up, right? So I started reading.

From there, I started looking through other similar webcomics, finding more and more furry things, until I realized I liked it all enough to call myself one. I ended up lurking in various furry spaces on the internet for around 5 years, just kind of getting acquainted by osmosis. Eventually, when I went off to college, I got into contact with other furries at the university I attended, and they convinced me to start attending meets and such. From there, it snowballed into us creating a furry club at the university together and I dived head-first into the thick of it.

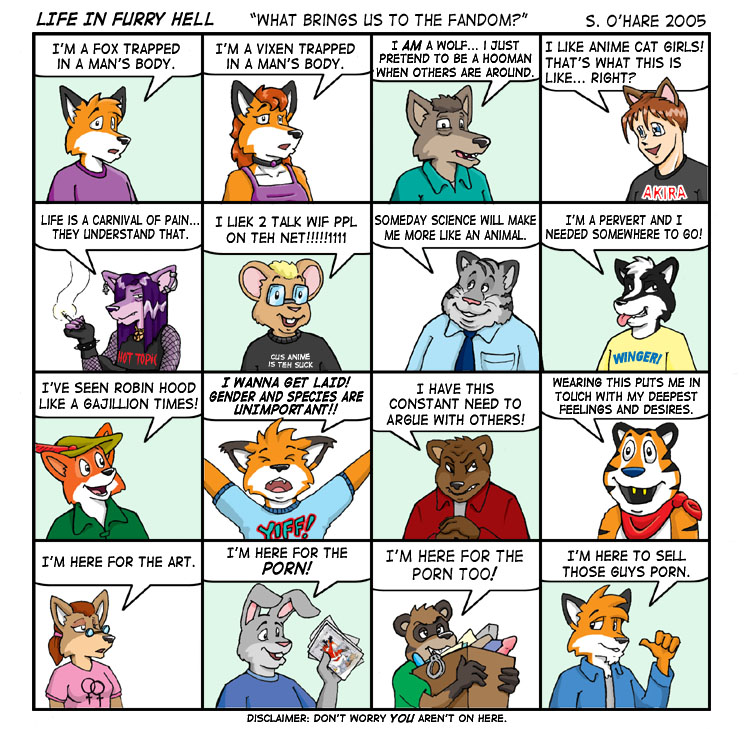

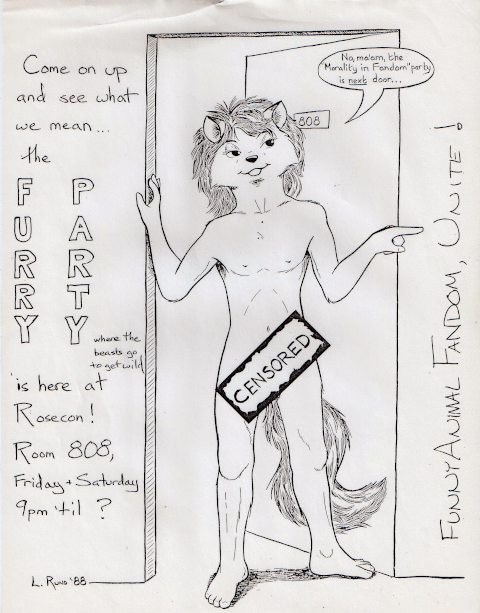

Now, that story is entirely true, but... it leaves some things out. It leaves out the late nights I spent nervously typing "werewolf" into a Google search bar and hungrily wolfing down every possible suggested search Google gave me. It leaves out my wider state of mind at the time. It leaves out any discussion of NSFW elements -- though I acknowledge that for this kind of story and given the fact that I was a minor at the time, perhaps that's for the better, even despite that aspect's significant personal importance. It leaves out this image:

For me, there was something more than just "Oh, this art is neat!" that drew me to the fandom. Images like the one above, funny joke that they may be, unfortunately dissuaded me from poking at that for years. And even now I'd say I'm pretty reticent to elaborate on exactly what that draw is. The cat, in box 7, particularly lingered with me, and the mocking pity I assumed we were supposed to feel for him. Knowing what I know now, I understand what the significance to myself of that nervous energy strip-mining Google for anything werewolf related is and was much better. I've mentioned elsewhere that I'm a therian, but I'll point out briefly; before that community called itself "therian", they were "weres", first congregating on the Usenet group alt.horror.werewolves.

Stories of the non-human

At the same time as I read Cracked regularly, I also remember reading this essay: "The Hidden Message in Pixar’s Films". This essay discusses a running theme that the author, Kyle Munkittrick, had noticed in Pixar films (the essay being written in May 2011, the most recent Pixar film at that time was Toy Story 3, with Cars 2 imminent). Particularly, Munkittrick focuses on how Pixar films address humans, and to discuss that, Munkittrick starts by considering The Lion King:

To understand Pixar films, one must first to go back to Disney before Toy Story was released –- to be precise, The Lion King. On top of being my favorite Shakespeare adaptation, The Lion King is the only Disney film to date with zero references to the existence of human beings. [...] Save for the fact that Zazu knows "I've Got a Lovely Bunch of Coconuts," there is no evidence that the characters within The Lion King even know humans exist.

Munkittrick explains that, though some Disney movies (e.g. Robin Hood) feature only animals, they're still extremely anthropomorphic, wearing clothes and drinking out of cups and so on; others feature humans less (e.g. The Jungle Book), but still have them around in parts. But Disney rarely just jettisons humans and human culture entirely, and Pixar follows in those footsteps.

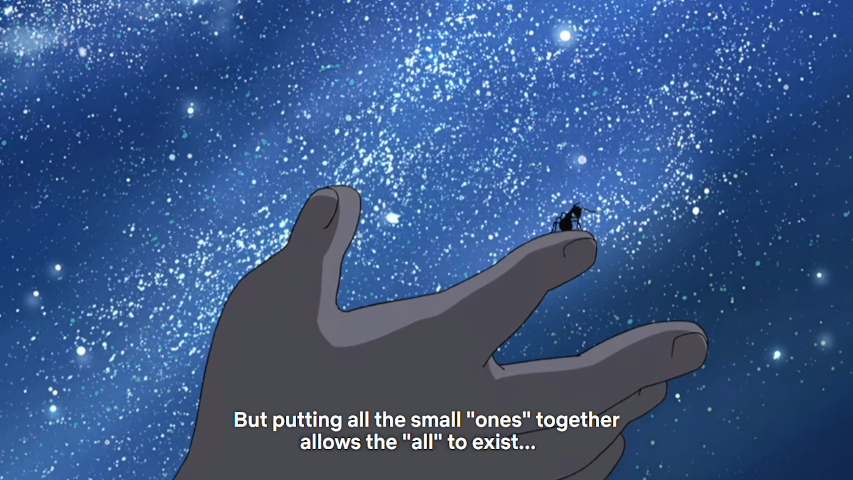

Instead, Munkittrick argues, Pixar movies follow a general rule. Ignoring Cars, Pixar movies (at that point) typically took place more or less in our ordinary world, but wherein humans are not the only intelligent beings. Munkittrick partitioned the movies into two distinct sets: "Human as Villain" and "Human as Partner". In Toy Story 1, 2, & 3, A Bug’s Life, and Finding Nemo, the protagonists are all non-human beings, and humans are, if not outright villainous, a non-beneficial part of the environment the protagonists find themselves in. These are the "Human as Villain" movies. On the other hand, in WALL•E, Ratatouille, and Up!, the protagonist is still a non-human being but befriends humans along the way to completing their story; these are the "Human as Partner" movies.

From here, Munkittrick goes on to discuss what he sees as "the point" of building a canon around the idea of non-human sentience. Largely, he sees it as building a larger rationale for extending the rights of personhood beyond humans and the need for humans to recognize the intelligence of other species:

Particularly in WALL•E, Ratatouille and Up! there is no ambiguity about the reality of intelligence in the non-human characters. Each Pixar film asks us to accept one deviation from our reality. While it seems like the deviation is different in every case (e.g. monsters are real, robots can fall in love, fish have a sense of family, Kevin is a girl, a rat can cook), the simple fact is that Pixar only asks us to accept one idea over and over and over again: Non-humans are sentient beings. That is the central difference between Pixar’s universe and our current reality.

Certainly, I think this is a fair point, albeit I don't quite share his level of enthusiasm for the subject. I wouldn't, as he does later on in the piece, call the idea of extending personhood to animals "likely this century's main rights battle". It was a bad claim to make only 11 years into the century, and it only falls more flat now as protests for civil rights happen nationwide and beyond, despite being in the middle of economic and medical crises. But, insofar as the lines between "human" and "animal" are at best hastily drawn, I would agree.

Linguists would have you believe that language differentiates humans from other creatures. Sure, there is bird song, and dolphin speak, and all manner of other communication that we... don't fully understand. But we think it's different, lesser than our own. And anyways, if not language, then sentience separates us... yet the more we understand about animals, the more we realize we have grossly underestimated their interiority. Did you know that animals get bored? What we have applied the scientific label "enrichment" and "stimulation" to, we really mean, we have found that animals need and seek out entertainment and play just as humans do. So, if not language, if not sentience, then scientists would have you believe that tools more generally are what separate us, even as primates and corvids are well-observed to use them as well. Agriculture and domestication is not exclusively human, when ants farm aphids. Not even fire, that Promethean implement we trace our origins long, long ago to, is solely our own. Fire-foraging birds take advantage of and spread fire in order to hunt; the lodgepole pine not only needs fire in order for its seeds to spread, but actively encourages fire to start, as older trees die and dry out so that their offspring may take root after the ensuing blaze.

Humans do, of course, have some significance that is difficult to place exactly. I don't mean to imply that there are no differences between humans and other animals. Humans are animals, of course, but also we have positioned ourselves such that we can do a lot more harm to the world around us right now than anything else can. Whether we could destroy it totally is difficult to say; life, uh, finds a way. The trees did not manage to end life in the Late Devonian extinction. But, it is a danger to be aware of. That being said, it's also deeply arrogant and foolish to overlook the other entities we share this planet with. After all, we are animals. We live in an environment, even if we have altered certain parts of it in drastic ways. We are a part of an ecology, one cog surrounded by many other pieces that we depend on and that react to us. But we'll come back to this.

A sense of place

A YouTube video I watched recently by Philosophy Tube features a useful and concise explanation of the concept of "alienation", admittedly itself borrowed from the play Young Marx. In a fictional anecdote supposedly from Karl Marx's life, Karl Marx comes to an epiphany while making breakfast and staring at an egg. "I don't know who laid this egg!" he exclaims.

Specifically, as the story goes, what he meant by the exclamation was that at one point in human history, a person cooking eggs and sausage for breakfast would know where they came from. That is, they would know the person who assembled the sausage, they would know the chicken keeper who harvested the egg. The sausage itself, in some sense, can represent the social connections a person has in their life. Now, under a capitalist society, his only connection to those individuals is through cash; he exchanges cash at a market that is taken by a vendor and back down the chain eventually it lands in the hands of the people who actually made these things.

Cash can't tell us anything about our connections to other human beings. By necessity, it is completely exchangeable; there is nothing special in particular about this or that dollar bill. And that removal of those connections, that forced distance from these people that we would otherwise have some form of social bond with, is alienation. We don't get people, we get products, and it's easy to forget about the people who are still behind the scenes making the things we consume when we only interact with product all our lives. What are their lives like, working with the animals, farming our food? Are their working conditions safe? What are their problems? What if we have the same problems? What if those problems have the same political causes?

Alienation obscures and abstracts away the shared experiences we as people have. And it is necessarily so; if we don't recognize that shared experience, the problems we face, and how we could come together to make them better, then we can't effectively disrupt the system that causes these problems. Alienation from labour is a very important concept to Marxist thought.

Alienation, though, is not limited to our understanding of labour. Consider this. I grew up in the country. By which I mean, the house I lived in growing up was not inside the boundaries of any village, town, or city; our address featured the name of a small village (population \~300) nearby, where we went to pick up packages if the USPS needed a signature, but otherwise we were... just out there. The land on the other side of the road from that house was, until a few years ago, a field that a farmer grew hay on. As a kid, I remember that when they would bale the hay, me and the kids who lived vaguely near us would go out and climb on top of the bales. Haybales, to a 4 year old, are very large things to climb. Given all this, I've always felt some divide between myself and "city kids" as a result of our divergent experiences growing up.

Now, don't get me wrong, I still always went to school in the city, about a 30 minute drive from that house. I did a lot of the "city kid" things, and missed a lot of the "country kid" things. I was always kinda a nerd and so, I played with computers and video games all the time growing up, despite our family having dial-up through the mid-to-late 2000s. But also, every summer as a kid, I'd see the progress of the corn and soybean fields growing when we drove into town. I'd see how, due to the very, very flat nature of that part of the world, you could go out in the middle of the winter and look in any direction and see for dozens of miles. As I grew older, I came to understand better the history of that place, what it had been and how it came to be what it is now. I had what I would call a sense of place.

But often, we do not know the histories of the places we visit and live, especially cities. We do not know how the geography of a place impacts what shape life takes there. We are only fuzzily aware of weather as a thing that happens, not of the connection the land around us has to that weather. I worked an internship one summer in New York City. That place exists in the middle of miles upon miles of concrete. What that land had once been is now completely gone. It has formed a new place unto itself of sorts, but that connection to what it once was is wholly severed. I couldn't stand living in all that concrete, so separated from anything outside of what humans had constructed for themselves. I was alienated from the place it had been. A lot of the "city folks" tropes, I think, derive from such an alienation from land more generally.

Neil Evernden, in his 1978 essay "Beyond Ecology: Self, Place, & the Pathetic Fallacy", writes about exactly this feature of city life:

The assumption that there is such a thing as a sense of place brings to light some strange anomalies in our current lifestyle. For instance, we must ask ourselves whether it is truly possible for any creatures in a state of sensory deprivation to form genuine attachments to place. What is the experience one has of an urban environment? What do we see? What do we smell, or hear? Contrary to those who praise the complexity of urban life, I must insist we take seriously Kvaløy’s distinction between the complex natural environment and the merely complicated urban one. The environmental repertoire is vastly diminished in urban life, perhaps to the point of making genuine attachment to place very difficult -- even assuming a person were to stay in one place long enough to make the attempt at all. In lieu of the opportunity to form a relationship to place, the urbanite is easy prey to the advertisers who promise an easy surrogate, a commercial sop to his need for place, both social and physical. He is encouraged to accept the social place that comes, free of extra charge, with the commodity in question. But an automobile is no real substitute for physical place, no adequate extension of the self, or one so limited in potential as to hopelessly limit the emotional repertoire of the symbiont.

Evernden talks directly about the consequences of this alienation. Instead of a relationship to place, he says, under capitalism, we might find ourselves easy prey for advertisers and salespeople, selling us things to try to fill that gap. Others might look askance at how he also discusses this alienation in terms of sensory deprivation, as if in a city we cannot see, smell, or hear. And of course, we know that cities come with all manner of sights and smells and sounds, but he means specifically: How do we perceive nature when we are in a city? It's there, but it's much harder to notice than when we are out among the "wilderness".

Alienation from nature

That is to say, Evernden effectively describes the alienation from place I was discussing in terms of another important alienation, that from nature more generally. Consider the following question: in your body, what part is you? In Western philosophy, that question for a time was answered as "your mind" or "your soul", some entity entirely separate from your body. Descartes specifically believed that a person's soul was joined to their body through the pineal gland, a small gland inside the brain. We use "mind" at times to describe what we essentially mean as our brain, so we could use that as our answer, but that's still fundamentally the same. In such a supposition, "you" means "some specific subpart of the body you inhabit", and "you" drives the rest of the body like a lumbering flesh mecha.

If we don't suppose that we are wholly separate from our bodies, then we come away with a slightly different picture. Of course, our bodies do not wholly determine us. Over time, we may even find reason to alter things about our bodies, whether they be smaller things, like tattoos and piercings, or larger changes, like hormone therapy and surgeries. However, our bodies play some role in making us "us". Were we to consider non-human animals, I think it is much less controversial to suppose that the part of, say, a dog, that is "that dog" spreads all the way out to the skin and fur of the creature.

But, for a moment, consider instead the cichlid, a small fish. As Evernden writes:

Normally, size is of considerable importance -- the big guy usually gets his way. But when the breeding season comes along, strange things start to happen; size does not necessarily prevail. It appears that once a small fish has established himself in a territory, he goes quite mad. That is to say, he does not appear to behave rationally. He doesn't seem to respect size at all. He even seems to forget what an insignificant specimen he is, and will attack a much larger intruder. In short, it's as if he thinks he is as big as his territory. It's as if his boundary of what he considers to be "himself" has expanded to the dimensions of the territory itself. The fish is no longer an organism bounded by skin -- it is an organism-plus-environment bounded by an imaginary integument. The boundary isn't a sharp one, but rather is a gradient. The further you get from its center, the less willing is the fish to attack. It's as if there is a kind of field in the territory, with the "self" present throughout but more concentrated toward the center.

The fish, one could imagine, almost sees itself as the entire territory it sits within. It only directly manipulates the fish part, and sees through the fish's eyes, but it is a component of a larger whole. In many ways this is exactly the sorts of concepts ecology as a scientific endeavour is meant to give us. We know that we live in an environment, as one piece in it while so many others do as well. To briefly return to Munkittrick's wheelhouse, The Lion King tells us as much in its opening number!

Under our normal living conditions, it is my observation that, commonly, we humans see nature as more or less "separate" from ourselves. We often highlight nature as a thing that happens in National Parks, or other set-aside lands. We go out of our way to go to these places that people are not allowed to develop and extract resources from, or tear down and build concrete towers atop. We call these places "wild", because they are untamed by us, separate from us. William Cronon, in his 1995 essay "The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature", details the history of the American concepts of "wilderness" and "nature". Perhaps the most striking portions of the piece are where he talks about the deliberate artifice of the idea of wilderness being "a place untouched by humans":

The myth of the wilderness as "virgin" uninhabited land had always been especially cruel when seen from the perspective of the Indians who had once called that land home. Now they were forced to move elsewhere, with the result that tourists could safely enjoy the illusion that they were seeing their nation in its pristine, original state, in the new morning of God's own creation. [...] Once set aside within the fixed and carefully policed boundaries of the modern bureaucratic state, the wilderness lost its savage image and became safe: a place more of reverie than of revulsion or fear. Meanwhile, its original inhabitants were kept out by dint of force, their earlier uses of the land redefined as inappropriate or even illegal. To this day, for instance, the Blackfeet continue to be accused of "poaching" on the lands of Glacier National Park that originally belonged to them and that were ceded by treaty only with the proviso that they be permitted to hunt there.

Cronon argues elsewhere that, in fact, "wilderness" is entirely a construct of humanity; after all, if we continue to define it in terms of ourselves, even an absence of ourselves, the definition loses meaning if we don't exist. And worse still, separating out our understanding of what nature is to these specific places, these carefully bounded off locales that we can go and visit and then retreat back to civilization means we completely blind ourselves to the inescapability of nature! After all, ask anyone in San Francisco right now whether or not they're aware of the nature around them. Or ask New Orleans circa 2005 if they are separated from nature. Ask Anchorage in 1964.

Natural disasters are only the most undeniable assertions of nature into the sphere we call "civilization". Nature is always all around us. Consider the raccoons of Toronto. Though the city proudly trumpeted its "raccoon-resistant" garbage disposal bins, it was only a short matter of time before clever raccoons figured out how to break in anyways. Elsewhere in cities, coyotes thrive in the in-between spaces that humans are unable to oust them from. Plants grow, not always where they're supposed to (sometimes, with human assistance). Weather happens, whether we like it or not. And the climate at large can and will have dramatic effects on nearly every aspect of our lives, whether we admit we are altering it or not. To feel a disconnection from the nature around us is understandable; it is a condition of the way we have structured our society that we are constantly alienated from it. But to deny that we find ourselves in the middle of nature all the time is either naïveté or arrogance.

Why does this matter?

Perhaps I have convinced you that alienation from place and from nature are noteworthy. But, why is it actually bad? Consider what Cronon has to say:

This, then, is the central paradox: wilderness embodies a dualistic vision in which the human is entirely outside the natural. If we allow ourselves to believe that nature, to be true, must also be wild, then our very presence in nature represents its fall. The place where we are is the place where nature is not. If this is so -- if by definition wilderness leaves no place for human beings, save perhaps as contemplative sojourners enjoying their leisurely reverie in God's natural cathedral -- then also by definition it can offer no solution to the environmental and other problems that confront us. To the extent that we celebrate wilderness as the measure with which we judge civilization, we reproduce the dualism that sets humanity and nature at opposite poles. We thereby leave ourselves little hope of discovering what an ethical, sustainable, honorable human place in nature might actually look like. [...] [W]e seem unlikely to make much progress in solving these problems if we hold up to ourselves as the mirror of nature a wilderness we ourselves cannot inhabit. To do so is merely to take to a logical extreme the paradox that was built into wilderness from the beginning: if nature dies because we enter it, then the only way to save nature is to kill ourselves. The absurdity of this proposition flows from the underlying dualism it expresses. Not only does it ascribe greater power to humanity than we in fact possess -- physical and biological nature will surely survive in some form or another long after we ourselves have gone the way of all flesh -- but in the end it offers us little more than a self-defeating counsel of despair. The tautology gives us no way out: if wild nature is the only thing worth saving, and if our mere presence destroys it, then the sole solution to our own unnaturalness, the only way to protect sacred wilderness from profane humanity, would seem to be suicide. It is not a proposition that seems likely to produce very positive or practical results.

Today, in the year 2020, understanding Earth as our home, the only one we've got, is a belief perhaps more widely held than in 1995. We know that we need to take care of our home and find a way to live in it that can continue for generations. Cronon argues that, really, as part of getting into this mindset, we need to be ready to understand how we are a part of nature everywhere. If nature is only ever something "out there", we both are deliberately keeping ourselves from realizing we have skin in the game, and unable to look forward to solutions other than the "counsel of despair", or what we might now call eco-fascism. And in the same way we must face down alienation from labour, we must face down our alienation from nature in order to recognize our shared experiences as beings on this planet, the problems we face, and how we can come together to make them better, so that we can effectively disrupt the system that causes these problems.

Evernden speaks similarly to Cronon, but directs his attention more to the role place has in making a person more invested in questions of the usage of resources:

Given this, one who looks on the world as simply a set of resources to be utilized is not thinking of it as an environment at all. Such a man is, according to Sparshott, "blind to all the aspects that make it an environment." The whole world is simply fodder and faeces to the consumer, in sharp contrast to the man who is in an environment in which he belongs and is of necessity a part. The tourist can grasp only the superficialities of a landscape, whereas a resident reacts to what has occurred. He sees a landscape not only as a collection of physical forms, but as the evidence of what has occurred there. To the tourist, the landscape is merely a facade, but to the resident it is "the outcome of how it got there and the outside of what goes on inside." The resident is, in short, a part of the place, just as the fish is a part of the territory.

Nobody likes a tourist, and a person who cannot appreciate a place beyond its utility is never more than a tourist anywhere they go. To understand a place, to see how actions over the course of a lifetime or longer may effect that place, and how this determines the world we leave after ourselves, we have to be resident. Whereas class consciousness is the tool with which we break alienation from labour, living in a place -- understanding it, its history, how it functions, and how we fit into it -- is how we break alienation from place.

The indigenous anarchist Aragorn! writes about the importance of place in his 2005 essay "Locating an Indigenous Anarchy". He takes as one of his first principles for such a philosophy that "[a]n indigenous anarchism is an anarchism of place", noting: "Location is the differentiation that is crushed by the mortar of urbanization and pestle of mass culture into the paste of modern alienation". "Modern alienation" is a multi-faceted thing, and we might interpret Aragorn! to be referring to several different alienations simultaneously. The effects of urbanization and mass culture have been to make many places effectively interchangeable, with only minor caveats. Sure, Austin, Texas, is hot and Portland, Oregon, is temperate. But culturally, we might view them fairly similarly. And that inability to really understand the differences between places is one symptom of this wider alienation we experience, that crushes us down.

Animism and alienation

So, if we suppose this alienation is real, and that it is a problem, the question remains: What are we to do about it? I mentioned that Evernden discussed being resident (similar to how Aragorn! describes indigeneity, by which he notably does not exactly mean "things that are native") as one answer. Aragorn! writes cryptically at times, but the first "first principle for indigenous anarchy" he discusses gives us another concrete idea:

Everything is alive. Alive may not be the best word for what is being talked about but we could say imbibed with spirit or filled with the Great Spirit and we would mean the same thing. [...] The counterpoint to everything being filled with life is that there are no dead things. Nothing is an object. Anything worth directly experiencing is worth acknowledging and appreciating for its complexity, its dynamism and its intrinsic worth. When one passes from what we call life, they do not become object, they enrich the lives they touched and the earth they lie in.

The view that everything is alive, or "imbibed with spirit", is perhaps recognizable to you as "animism". Aragorn! briefly touches on why such a view has value, talking about how we can acknowledge and appreciate the complexity of other things when we recognize that the spark of life resides in them as it does us. And when things pass on from life, they still have an importance, in how they continue to effect us in memory, and how their bodies effect the world they rest in.

As one small example of what animism might look like, consider this. When you, say, eat a mushroom, you might thank it. You wouldn't do this because the mushroom (or anything else) will hear you and appreciate it. Rather, you would do this, because the mushroom had a life separate from you, that you have taken for your own needs. From time to time, this must be done; it is how life operates. But the mushroom wasn't for you. It existed on its own terms. Now, it feeds you, and has become a part of you. To thank the mushroom is to remind yourself of its existence separate from you.

Evernden also argues that animism has value and relates it more directly to alienation:

What does make sense, however, is something that most in our society could not take seriously: animism. For once we engage in the extension of the boundary of the self into the "environment," then of course we imbue it with life and can quite properly regard it as animate -- it is animate because we are a part of it. And, following from this, all the metaphorical properties so favored by poets make perfect sense: the Pathetic Fallacy is a fallacy only to the ego clencher. Metaphoric language is an indicator of "place" -- an indication that the speaker has a place, feels part of a place. Indeed, the motive for metaphor may be as Frye claims, "a desire to associate, and finally to identify, the human mind with what goes on outside it, because the only genuine joy you can have is in those rare moments when you feel that although we may know in part... we are also a part of what we know."

Evernden's view of animism is related, although it seems to come more from an egoist perspective. That is; whether or not we can allow for the idea that things have their own spirit, perhaps we can allow instead that we ourselves imbue them with spirit, as a part of ourselves. The environments we pass through and live in, after all, may be viewed as a part of us as well. If we were to let ourselves see spirit in the world around us, whether it comes from us or not, we are working to root ourselves into that place. And, importantly, as one avenue to do so, the "Pathetic Fallacy" Evernden is discussing here is a particular form of, well... anthropomorphization.

Towards a furry ecology

And so, we finally find ourselves full circle. In discussing the canon of movies Pixar had produced by May 2011, Munkittrick saw the value of the studio's portrayal of anthropomorphic non-humans directly for guiding us in recognizing the life of beings other than humans. Yes, he saw it in terms of an intelligence humans might regard as their peer, but we needn't restrict ourselves so. Evernden, elsewhere, discussed more directly how he saw art and the humanities as being involved in this process:

The "deep ecological movement," the one that concerns itself with the underlying roots of the environmental crisis rather than simply its physical manifestation, demands the involvement of the arts and humanities. Yet it is the members of those disciplines that seem least frequently involved, with, as I said before, some very notable exceptions. In part this may be due to the reluctance of society to pay attention to anyone who is not a scientist. It may also be partly due to a fear that anyone interested in animals and flowers will be labeled a Romantic. But I fear it stems in part from the old assumption that the proper study for man is man. In accepting this, artists and humanists borrow from the sciences whose reductionism they so often criticize, for to suggest that man can and should be studied exclusive of his environment is as good an example of reductionism as we are likely to find. Hence, there is man, and there is environment. The humanist need feel responsible only for man. If there's a problem with the rest, call in a scientist. Indeed, even the suggestion that man is tied to anything but himself, or that he shares any biological imperatives with other creatures, is seen in some quarters as an affront to humanity. This is doubly unfortunate, I think, for not only does it bespeak a regrettably low opinion of the rest of creation, it also alienates from the environmental movement a portion of the population that could be its most potent force.

Evernden's words, particularly talking about the idea that humans are in any way like other animals being an affront to some individuals, rings loudly to me. He calls such ideology a "regrettably low opinion of the rest of creation"; can we as people not appreciate the other beings with which we share our home? Certainly, there is one group among us, one set of people who have well acquainted themselves with the tools of anthropomorphism, and who might call their raison d'etre precisely that appreciation.

Not every furry, it should be noted, would find themselves advocates of ecology in quite this way. Furry is an extremely varied group, with any number of reasons one might find themselves a part of it. And, after all, though we do celebrate an appreciation of animals of a sort, it's true that... what we celebrate is a fiction. Wolves in our world do not walk on two feet and speak with us. That's not likely to change anytime soon. I do not ask all furries to agree with me on the worldview I am here espousing, nor do I ask you to assume that furry necessarily leads to such a philosophy.

However, what I am proposing is that furries are, in general, not so far away from being able to view the world in terms of such spirit. We already commit much of our time in thinking about animals in one form or another; is it really such a stretch that our appreciation of explicitly anthropomorphic animals could help us to view the animals of our own world in a new light? Is it so unbelievable that we can learn to recognize their existence as something unto itself and understand that they have their own view and experience of the world? We may or may not extend legal personhood to them. Certainly, though, we can try to imagine in some capacity what it feels like to live in the world as they do, and that that life has its own value, separate from us.

At times, we may come into conflict with other life: I do not ask you, for example, to forego eating meat. I still eat meat. But we can appreciate that even the animals we eat had a life, and that that means something. As with my "thanking the mushroom" example previously, when we consume them, we have taken something from them. That, at least, we can acknowledge and respect.

Some among us may take this even further. I mentioned earlier that I am a therian. I can appreciate the life of other beings on their own merits despite their non-humanity; perhaps there is some relationship to that appreciation in that I also view myself to have some level of non-humanity. But this is not necessary for the general principle to apply, I believe. I do not think it is a necessary requirement for us to renounce the human in ourselves in order to see the world around us as alive.

If there's anything I would ask of you, it's that you keep this idea in the back of your mind. As you view art, or read stories, or interact with furry in any manner you prefer, there is a temptation to separate that from the rest of life. It is a fiction, after all. And yes, it would be foolish to ascribe to, say, foxes of the real world the same stereotypes we do of fox characters within the fandom. But, perhaps, you can let yourself see in those characters something that transfers over to the real world. If you are ever so lucky as to meet a fox in our world, then perhaps you can appreciate its life separate from you. You can appreciate the very different way it experiences the world, perhaps even imagine what it might be like to experience it yourself.

It is important to remember that, in relation to the danger humanity poses to the earth and other life, it is... not exactly the case that humanity itself is what poses that threat. The Machine, the power and wealth that seeks to preserve itself no matter the cost, poses this threat. And, whether we realize it or not, we have internalized the Machine, we believe that the Machine is what we are. And so, in upholding this system, whether you call it Capitalism or some other name, we separate ourselves from nature. Sometimes we materially benefit from our participation in the Machine, particularly the already-privileged among us. Too often, though, we grind ourselves to dust, all the while believing we are fulfilling some cosmic role we were meant to play.

To counter this, in imagining what it might be like to, say, experience being a fox yourself, you can work to understand yourself as just one piece of the world and ecosystem we find ourselves in. You can begin to see how the Machine harms both ourselves and the other beings of our planet. You can appreciate that the Machine does not have to be who you are, and that for us all to break free and prevent further damage to our home, we must make drastic changes to our society. And when it comes time to make these drastic changes, we can give voice to the beings humans can't otherwise hear. How can we live together with the rest of the planet? It may be our only home, but it is theirs as well. We would do well to remember that, lest we destroy all the things that make it our home in the process of "saving" it.

Comments

Feel free to share your comments here. I approve each comment before it becomes visible. Sorry if this doesn't happen quickly; I have other stuff going on sometimes. Use common sense about what to post; no racism, no sexism, no homophobia, no transphobia, and so on. Be good to each other, that is. If you format your comments in Markdown, they will be rendered when they get put up on the site (though some features, like images, are not supported).

There are currently no approved comments.

make comment